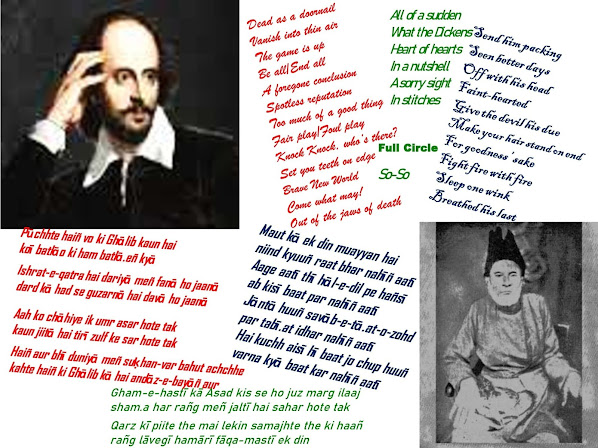

Shakespeare for laymen and Ghalib today (Part Two of both)

Readers may recall my blog post on Shakespeare wherein I had said that I, like a million others, have been left spellbound by the bard in his simple creation of nearly 2000 words and phrases which we, mostly unknowingly, speak even today. I had presented some examples of what all we say today which we owe to Shakespeare, delving in bit into the background. I had said that I had merely scratched the surface, only a handful from the vast treasure. The blog link:

http://anindecisiveindian.blogspot.com/2021/03/shakespeare-for-laymen-like-me.html

Readers may also recall my blog post on Ghalib and his contribution in making our day-to-day language colourful and forceful. The blog:

http://anindecisiveindian.blogspot.com/2021/04/ghalib-today.html

Or if you watch the YouTube channel thepublic.india, my programme on Ghalib’s versatility covering some shers in everyday use:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yRk38wWTDhE&t=739s

I had promised that I would continue it as a series with more blogs or sessions on YouTube, so here goes the second one, with gems both from granduncle, the bard and chacha, our own Ghalib. Enjoy!

|

Shakespeare’s

original text and context |

Phrase/idiom in use |

|

Edmund tells Edgar as the former says that they should forgive each

other, “Thou’st spoken right. 'Tis true. The wheel is come full circle. I am

here.” |

‘Full circle’ means

when events complete a cycle and one is back in the situation they were in

earlier. |

|

Falstaff to Prince Henry in Henry IV Part 1 who

wants an old man sent on his way, “Faith, and

I’ll send him packing." |

‘Send him packing’

means to send someone away by persuasion or force. |

|

Hamlet sees his father’s ghost and says, “My father’s spirit in arms. All is not well. I doubt some foul play.” |

‘Foul play’ is

used when one suspects some nefarious or illegal actions at hand. |

|

Macbeth says in aside, “Come what come may,

Time and the hour runs through the roughest day.” Meaning, one

way or another, what’s going to happen is going to happen. |

‘Come what may”,

today, however, is used in the sense of no matter what happens. |

|

‘Too

much of a good thing’, now-a-days is used to express about excess of any desirable thing which may do

harm. |

|

|

Belarius says in Cymbeline, “that am Morgan

call'd, They take for natural father. The game is up.”, in the sense that the game was over and all

was lost. |

Now-a-days ‘The game is up’ has come to be used to mean that

one had seen through through the tricks and the deceit was exposed'. |

|

Anatomically

happy expression, coined by the bard in Hamlet when Hamlet says to his friend

Horatio, “That is not passion’s slave, and I will wear him, In my heart’s core,

ay, in my heart of heart, As I do thee.” |

‘Heart

of hearts’ means what you really believe or know although outwardly you may

not say or show it. |

|

Othello says to Iago in Othello, “But this denoted a foregone conclusion" when the former is building false circumstantial evidence about Cassio and Desdemona. |

‘A

foregone conclusion’ refers to a decision made before any; i.e., it is a conclusion which

is inevitable because the result has been decided beforehand. |

|

The bard coined this

phrase in Henry VI when Somerset says, “Come quickly, Montague hath

breathed his last.” |

‘Breathed

his last’ is a a euphemism, a nicer way of saying that someone has died. |

|

In The Taming of The Shrew, Tranio, wondering if a

person could fall in love so quickly, says, “I pray, sir, tell me, is

it possible, That love should of a sudden take such hold?” |

‘All

of a sudden” describes an unexpected event that happened without forewarning or

simply to refer to an event that was unanticipated, a poetic way of saying suddenly. |

|

The bard came close to this phrase in

Othello, when the Clown says, “Then put up your pipes in your bag, for I'll

away. Go; vanish into air; away!” |

‘Vanish

into thin air’ means to disappear completely in a way that is mysterious. |

And now the chacha, Ghalib. As I said earlier, my objective here is not to decipher the abstruse nature of Ghalib’s poetry from this mediocre pulpit but to make it more accessible to my readers and friends. These examples are such as can excite you to use in appropriate situations and see for yourself how appealing and elegant your discourse can become. (Again, like last time, if you find the list too long, let me tell you, the list is endless and I have put together only a fraction; I suggest you read cursorily and pick up what you find useable).

|

Raat din gardish meñ haiñ

saat āsmāñ ho rahegā kuchh na kuchh ghabrā.eñ kyā |

A statement of fortitude.

|

|

Pūchhte haiñ vo ki Ghālib kaun hai koī batlāo ki ham batlā.eñ

kyā |

Cited, usually, in

self-glorification in a manner of grandstanding. |

|

ishrat-e-qatra

hai

dariyā meñ fanā ho jaanā dard kā had se guzarnā hai

davā ho jaanā (ishrat-e-qatra: pleasure of a drop) |

Employed to convey that too

much of pain itself turns into a cure. |

|

haiñ aur bhī duniyā meñ

suḳhan-var bahut achchhe kahte haiñ ki Ghālib kā hai

andāz-e-bayāñ aur (suḳhan-var: speakers, poets) |

Cited when praising the

unique qualities of oneself or someone else. |

|

Maut kā ek din muayyan hai niind kyuuñ raat bhar nahīñ aatī (muayyan: pre-determined) |

Recalled in case of

unnecessary worries.

|

|

Aage aatī thī hāl-e-dil pe

hañsī ab kisī baat par nahīñ aatī |

Expresses utter despair and

despondency. |

|

Jāntā huuñ

savāb-e-tā.at-o-zohd par tabī.at idhar nahīñ aatī (savāb-e-tā.at-o-zohd:

blessing of obeisance and piety) |

Spoken to convey that

obsequious behaviour, which can lead to rewards, is not one’s cup of tea |

|

Hai kuchh aisī hī baat jo chup huuñ varna kyā baat kar nahīñ aatī

|

Used tellingly when one has

decided not to speak out. |

|

Ham vahāñ haiñ jahāñ se ham

ko bhī kuchh hamārī ḳhabar nahīñ

aatī |

Spoken to express that there

is total confusion in one’s life. |

|

Asad bismil hai kis andāz kā

qātil se kahtā hai ki mashq-e-nāz kar ḳhūn-e-do-ālam

merī gardan par (bismil: injured,

mashq-e-nāz: practice of blandishment) |

A part of the second misra

is used in mock acceptance of all the blame. |

|

Jaate hue kahte ho qayāmat ko

mileñge kyā ḳhuub qayāmat kā hai goyā koī din aur |

Used with genuine emotion at

the time of parting with uncertainty about reunion. |

|

Aah ko chāhiye ik umr asar

hote tak kaun jiitā hai tirī zulf ke

sar hote tak (sar: untangle, straighten) |

Cited in case of prolonged

apathy.

|

|

Gham-e-hastī kā Asad kis se

ho juz marg ilaaj sham.a har rañg meñ jaltī hai

sahar hote tak (juz marg: except death) |

Used in somewhat sombre

situation to convey that one must suffer their afflictions silently while

sustaining succour for others. |

|

Mehrbāñ ho ke bulā lo mujhe chāho

jis vaqt maiñ gayā vaqt nahīñ huuñ ki

phir aa bhī na sakūñ |

Cited when one is ever ready

to come forward for help. |

|

Qarz kī piite the mai lekin samajhte the ki haañ rañg lāvegī hamārī fāqa-mastī

ek din (fāqa-mastī: cheerfulness in starvation) |

Conveys cheerfulness in

wasteful profligacy and adversity in a grandiose manner. |

|

Banā kar faqīroñ kā ham bhes Ghālib tamāshā-e-ahl-e-karam dekhte

haiñ (tamāshā-e-ahl-e-karam: games

played by the kind people of the world) |

Declared when one claims to

know many secrets and inside stories. |

|

Qāsid ke aate aate ḳhat ik

aur likh rakhūñ maiñ jāntā huuñ jo vo

likheñge javāb meñ (Qāsid: messenger) |

Employed to run down somebody

given to hackneyed answers. |

|

Mujh tak kab un kī bazm meñ

aatā thā daur-e-jām saaqī ne kuchh milā na diyā

ho sharāb meñ (daur-e-jām: a round of drinks) |

Expressing surprise and

casting suspicions over an unexpected favour. |

|

Tā phir na intizār meñ niiñd aa.e umr bhar aane kā ahd kar ga.e aa.e jo

ḳhvāb meñ |

Used to indicate long and

eager wait for someone or something |

|

Ghālib chhuTī sharāb par ab

bhī kabhī kabhī piitā huuñ roz-e-abr o shab-e-māhtāb meñ (roz-e-abr o shab-e-māhtāb: a cloudy day and a moonlit night) |

Used to indicate that one has

quit vices but still keeps them alive for occasions. |

|

Thak thak ke har maqām pe do chaar rah ga.e terā pata na paa.eñ to

nā-chār kyā kareñ (maqam: palce, nā-chār: helpless) |

When someone has become

scarce at a crucial time leading to many deserting the mission/gathering. |

|

Ghālib vazīfa-ḳhvār ho do shaah ko duā. vo din

ga.e ki kahte the naukar nahīñ huuñ main (vazīfa-ḳhvār: subsisting on royal grant) |

Spoken while ruing a new

found job in any employment, serving under someone. |

|

Dil-e-nādāñ tujhe huā kyā hai āḳhir is dard kī davā kyā hai

|

Used in jest in any seemingly

complicated situation. |

|

Ham haiñ mushtāq aur vo

be-zār yā ilāhī ye mājrā kyā hai (mushtāq: desirous, be-zār:

apathetic) |

Cited frequently to show

frustration over lack of response in spite of one’s keenness or the second misra

for any strange situation. |

|

Maiñ bhī muñh meñ zabān

rakhtā huuñ kaash pūchho ki mudda.ā kyā hai |

One says this when they are

not approached to speak their mind. |

|

Ham ko un se vafā kī hai ummīd jo nahīñ jānte vafā kyā hai |

Quoted in a situation of

false expectations from someone. |

|

Rañj se ḳhūgar huā insāñ to

miT jaatā hai rañj mushkileñ mujh par paḌīñ itnī

ki āsāñ ho ga.iiñ (ḳhūgar: habituated, rañj:

grief) |

When one wants to imply facing

so many difficulties that now everything seems easy. |

|

Ghālib-e-ḳhasta

ke baġhair kaun se kaam band haiñ roiye zaar zaar kyā kījiye

haa.e haa.e kyuuñ |

Used in real or mock

self-pity. |

|

Mai se ġharaz nashāt hai kis rū-siyāh ko ik-gūna be-ḳhudī mujhe din

raat chāhiye (ġharaz nashāt: intention of deriving pleasure, rū-siyāh: black-faced) |

Cited to strengthen one’s

statement of good intention or purpose which is hidden behind an apparent bad

reason. |

|

Gar ḳhāmushī se fā.eda

iḳhfā-e-hāl hai ḳhush huuñ ki merī baat

samajhnī muhāl hai (iḳhfā-e-hāl:

hiding one's condition) |

When one does not want lesser

mortals to follow what one is saying. |

|

Ishq mujh ko nahīñ vahshat hī

sahī merī vahshat tirī shohrat hī sahī (vahshat: mad frenzy) |

Used matter-of-factly when

someone else is prospering due to one’s hard work or off-beat actions. |

|

Qat.a kiije na ta.alluq ham

se kuchh nahīñ hai to adāvat hī

sahī (adāvat: enmity) |

Used in a humorous way to request

someone to keep in contact |

|

Ham bhī dushman to nahīñ haiñ

apne ġhair ko tujh se mohabbat hī

sahī |

A clever way of saying that a

rival's contact or interaction with a third person is fine (as I cannot be an

enemy of myself.) |

|

Umr har-chand ki hai

barq-e-ḳhirām dil ke ḳhuuñ karne kī fursat

hī sahī (barq-e-ḳhirām: walk like a

flash of lightning) |

Used to convey that although

one’s life is transitory, it’s enough to give one a bloodied hear or so much

pain |

|

ham koī tark-e-vafā karte haiñ na sahī ishq musībat hī sahī (tark-e-vafā: giving up

loyalty) |

Recalled when one wishes to

say that they would continue to tread the path they have chosen, irrespective of all the troubles on the way |

|

kuchh to de ai

falak-e-nā-insāf aah o fariyād kī ruḳhsat hī

sahī (ruḳhsat: leave , permission) |

Faced with repeated

injustices, one says that at least the leave to complain or plead should be

afforded to them. |

|

Yaar se chheḌ chalī jaa.e Asad gar nahīñ vasl to hasrat hī sahī | Cited when one is happy to be wistful in face of lack of success. |

(to be continued…)

indian sex stories

ReplyDeletedesi sex stories

bhabhi ki chudai

aunty ki chudai

jordaar chudai ki sex stories

hindi sex stories

sex kahani

bhabhi o jordar choda

aunty ko ghar meu chudai ki

kaamwali ko kaam krete huo chod dea