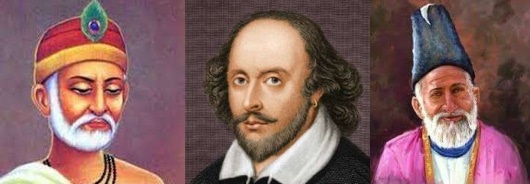

Management Lessons from Poet Uncles

I keep saying in my talks, in jest, that I was

hardly an accomplished speaker and

therefore keep borrowing from superior intelligence, usually my uncles: my great

grand uncle, Kabeer, who lived some 700 years back, my grand uncle, an

Englishman, Shakespeare, born more than 500 years ago and my young uncle Ghalib who started

speaking to me more than 200 years back. And indeed a battery of similar

kinspersons who have spoken so abundantly, meaningfully and elegantly that I

can simply forage and scrounge and perorate for hours on life, while keeping it

topical for this blog, most specifically on management and leadership.

Borrow and speak I will, but without disclaimers.

Because what I speak, and now write, about is gold standard on the ‘proof is in the pudding’ benchmark. They say that the stereotype leader-manager is a

specialist of spiel whereas a more seasoned and successful one goes one better

and writes. Now that I do both, and

also that I hardly have a leadership role anywhere, let me venture to write such

that all the articulation and diction are invariably supported by credentials

of actual accomplishment. Indisputable attainments by self, the team, someone else or some other entity.

The first thing I would say is directed at the leaders who

speak; speak a lot with high fives and suchlike. They have to be spoken to by Bendick, as he did in Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, “I would my horse

had the speed of your tongue.’’

In my entire service life, and believe it or not,

even as a consultant, I have wasted zillions of hours listening to leaders who

liked the sound of their voice. If it were merely a question of listening to

someone used to flapping his lips, it could be endured but the problem was that

most of these loudmouths were also given to exaggeration and haranguing. They

would offer lofty advisements, forgetting that if their achievements, if any,

were not guidance enough, their spouting homilies and diatribes would hardly

cut any ice. There was nothing that you really took away from them. Listening to

your leader yap away can also be pretty demoralising for all levels of earnest employees.

I have no panacea for dealing with such windbags and I guess organizational

compulsions would compel you to suffer them; I bring it up to caution you against becoming one yourself as you move up the ladder.

There is this barrage

of fatherly advice from Polonius to Laertes shortly before the

latter takes off for France and

most of it appears to be nothing but hackneyed banalities. Not to me. Let me

pick up some for the present

Give thy thoughts no tongue, Nor any unproportion’d

thought his act…

Give every

man thine ear, but few thy voice:

Take each

man’s censure, but reserve thy judgment.

I think this means that you need to make sure you listen to

everything that is said but you don't always want to be the one

saying things. Yes, keep

your thoughts to yourself, mostly, do not act rashly and be a good listener;

accept criticism but do not be judgmental. In time, you would know who is more

worth listening to and you can calibrate your listening. And further down, you

would also know who is worthy to hear of your thoughts and then you can start

sharing.

Falstaff is threatened

with imprisonment by the judge when he says, in Shakespeare’s Henry IV Part 2, “it is the disease of not listening,

the malady of not marking, that I am troubled withal.” The disease can be even

more intractable for a leader who has switched off listening to colleagues when

what they say seems to him trite or uninteresting. Leaders who show some of the

symptoms of this disease of not listening certainly have another problem: impatience

and haughtiness. A critique on this aspect too? We reserve it for future to see what poets say about it. For

the nonce, the takeaway is simple, listen and listen, think and think,

before you start speaking.

Let me give you an example of how leaders ought to

listen. I was a young officer, the in-charge of a diesel locomotive shed on

Eastern Railway, working really hard to improve the shed. Once the GM of the

zone was to visit the shed and we made elaborate arrangements, including a big

display of good work being done by us as well as bottlenecks and problems. The

GM, who had the reputation of a non-nonsense doer, was a patient listener. During the visit, the GM, with a

phalanx of underlings of varying seniority in tow, patiently viewed and

listened to whatever we had on exhibit, without demur, for close to 2 hours. He asked only a few

questions. After I was nearly done, he told me not to mention problems casually

to him but to name two problems, one which I thought a GM could and should

definitely solve, and another which I thought a

GM could definitely try to solve. I was

confounded by the uniqueness of the question but somehow regained my composure

and quickly briefed him on two pending issues; issues which I felt were certainly

doable but seemed like a mountain to me due to the sheer inter-dependability of

departments and funds involved. The GM spent some time understanding the same

and then congratulated me for giving him problems which he thought he could

solve. Then he had a cup of tea and left. And Lo and behold! Both the issues were solved by him before the third

month ended.

The learning from this great GM came in very handy in

my quest to know the people I was leading. I would play a game. As GM and

leader of Integral Coach Factory (ICF), I would sit with a group of officers

and ask them, one by one, exactly what was asked of me thirty five years back.

This helped me identify the doers in my team; the quality of the problem given

to me would tell me two important things, one, whether the officer understood

how things should and could work and two, whether he was actually interested in

problem-solving or was, in fact, a part of the problem itself. That was good.

What was not good were all kinds of problems that some officers presented. Some

problems which perhaps could not be solved by Modi ji himself, let alone a mere GM. One supreme moonshiner, a

very senior officer, told me that most of the blue-collar workers of ICF were

habituated to working four to five hours a day as this was the norm for the

past 40 years and the GM should decree and enforce that they work their eight

hours. Hark mine own lief GM! Thou art the panacea of all ills. Another gem I remember was when a

senior officer thought I had a magic wand; he advised me to order that each and

every material which went into making a coach, some five thousand of them,

should be made available all the time so no time was wasted in chasing stores,

in short, an industrial utopia.

Although some astute and savvy

officers always gave me immense hope through their answers, the not so

infrequent idiotic propositions from some senior officers were so amusing that

I often wondered if this exercise was worth it. Seeking intelligence from

people who did not know what wisdom was? Those who chase their own tails have

to be either booted out, or ignored and suffered in a way that they cause the

least damage. Ghalib has covered it

well in another sense so I modify it; the sense being simple, it is pointless

to try to reform the incorrigible and there would be some like that always, not

many but some, for sure.

Ham ko un se davā kī hai ummīd

jo nahīñ jānte

davā kyā

hai

(From them I hope for treatment

who know not what medicine is)

Then there were problems which an

officer himself could solve. To make the meeting enjoyable, and also to drive

the point home, I would ask these non-doer type problem-givers to assume that

they were the GM and then tell me their action plan to solve the problem; many

of them would cut a sorry figure, coming a cropper even before they started to

babble out an action plan. Like this industrial utopia gent could not suggest

any improvement to move towards his wish of 100% availability of materials all

the time. Well, in any case, most of the officers would start learning during

the course of the meeting and come up with problems which indeed could be

addressed. I not only got to know the ace doers and laggard non-doers of ICF, I

also had a huge list of problems to address and build an agenda.

Poets have their own

problems. Ironically, Ghalib, one of my icons for unravelling managerial

intricacies, frequently wrote what would be so mystical and magical that it

became inscrutable and abstruse for mortal intelligence. Aish Dehlavi, a

poet was so exasperated listening to Ghalib's difficult and

convoluted poetic expressions that he satirized in these lines:

agar apnā kahā tum

aap hī samjhe to kyā samjhe

mazā kahne kā jab

hai ik kahe aur

dūsrā samjhe

kalām-e-mīr samjhe aur zabān-e-mīrzā samjhe

magar un kā kahā ye aap samjheñ yā ḳhudā samjhe

(What’s the point if

your sayings are understood by you alone yourself. The enjoyment lies in one person

saying something and the other understanding it. Like listening to the poetry

of Meer and Mirza, two great poets. But the language of this worthy is in the

grasp of either himself or God almighty)

Ghalib was a master

poet. A manager can neither devise nor afford such dalliance or license and has

no option but to make himself clear to the meanest intelligence. Clear as a

bell. In any case, taking a cue from the master himself:

Ga.ī vo baat ki

ho guftugū to kyūñkar

ho

kahe se kuchh na huā phir kaho to kyūñkar ho

(Gone is the time when I

used to contrive of ways to speak, but, But talking has not helped so I am

perplexed about what to do)

“The world’s

mine oyster, which I with sword will open”, is, I

think, a sort of

threat by Pistol to Falstaff, in Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor, that the former would open people’s purses and retain the

riches for himself. I would, however, prefer a simpler interpretation for a

leader. His organization is his world and he must unriddle it fully to see what

lay inside. He has to keep his eyes peeled, his ears to the ground and his mind

wide open as if his charge was a riddle, wrapped

in a mystery, inside an enigma.

(to be continued with some more gems from the poet uncles…)

Nice read -

ReplyDeleteagar apnā kahā tum aap hī samjhe to kyā samjhe

mazā kahne kā jab hai ik kahe aur dūsrā samjhe

kalām-e-mīr samjhe aur zabān-e-mīrzā samjhe

magar un kā kahā ye aap samjheñ yā ḳhudā samjhe

The 'Mirza' here refers to poet 'Sauda' as per Shamsurahman Farroqi.

I once read a humorous rejoinder given below:-

वो भी कोई कविता है जिसको हर कोई समझे,

नहीं कुछ आर्ट है उसमे जिसे हर बेपढ़ा समझे,

वही कविता कलामय है, जिसे आलम तो क्या समझे,

अगर सौ बार सिर मारे, तो मुश्किल से खुदा समझे -

अगर सौ बार सिर मारे, तो मुश्किल से खुदा समझे -Kya baat hai! Thanks

DeleteThe most important advice in your blog is that before we take up our problems with our superior, we must first make sure that it is in fact in their schedule of power to help us. Also, vague complaints such as "No one is working", " Government policies are not good" etc must be avoided. One must state their problems/concerns as explicitly as possible.

ReplyDeleteYes, thanks

DeleteYes...thanks

ReplyDelete